Texas State develops in-house hand sanitizer to combat COVID-19

Mark Wangrin | May 28, 2020

When COVID-19 turned the world upside down in March and sightings of sanitizer became rare, Dr. Casey Smith realized it was time to take things in his own hands.

Smith, Shared Research Operations manager for Texas State University’s College of Science and Engineering, read that some area distilleries had converted production from craft vodka to hand sanitizer.

“We realized really quickly that we already missed the boat for ordering hand sanitizers,” Smith says. “We decided we would do this ourselves.’”

Smith, whose job is to make certain that Texas State’s research labs are clean enough to guarantee staff safety as well as uncompromised research, discussed synthesizing a home-brew hand sanitizer with Dr. Jennifer Irvin, associate professor of chemistry. They examined some recipes and turned to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) guidelines on hand hygiene and using alcohol-based hand rub (ABHR).

CDC recommends using ABHR with greater than 60% ethanol or 70% isopropanol (rubbing alcohol). Smith’s group used ethanol with an 80% standard.

“We targeted that to be a little higher,” Smith says. “We wanted to make sure if there was any evaporation of ethanol from the mixture that it was still well above the 70% threshold. That’s required to dissolve the cell walls and basically kill various kinds of viruses and bacteria.”

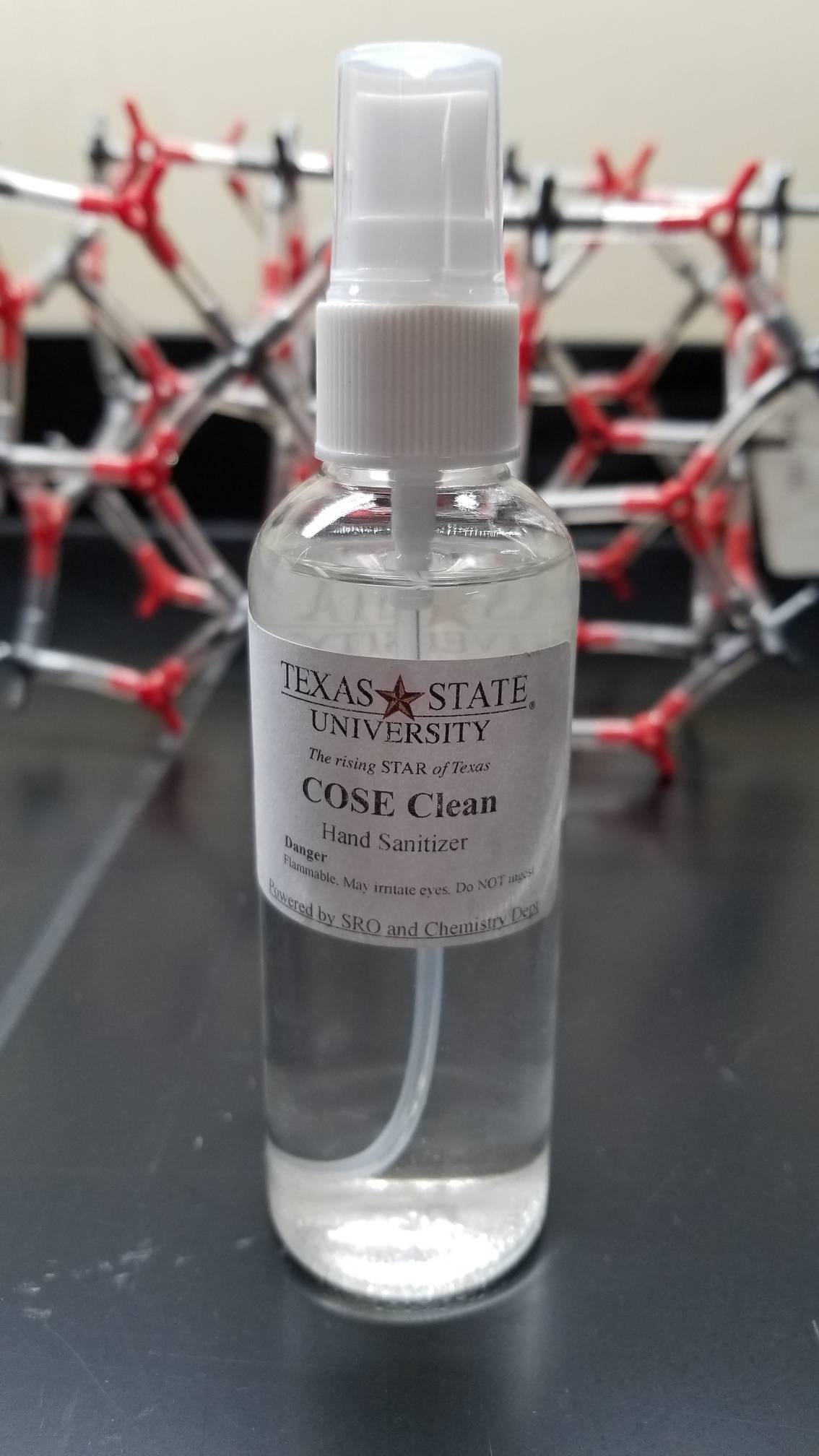

They also wanted the sanitizer to be applicable by a pump-spray container rather than in gel form, which tends to leave a stickier residue on the hands.

“It’s really only a couple of milliliters that are needed for application, so it gives it a lot more mileage in terms of how long it lasts,” Smith says.

They also wanted to make it as user friendly as possible, which is why they chose ethanol.

“Ethanol is less toxic compared to other alcohols,” Smith says. “Isopropanol is not something you want to be rubbing on your hands often and you certainly don’t want to use reagent-grade alcohol, which is ethanol mixed with methanol.”

“What does a whole lot of killing in the disinfectant wipes is something called quaternary ammonium salts (e.g. alkyl dimethyl benzyl ammonium chloride). These are added in very small amounts because they are somewhat dangerous, and some people develop skin reactions to these compounds. We wanted to make a DIY hand sanitizer using ingredients that were readily available, inexpensive, and posed little chance of sensitivity or an allergic reaction,” said Smith.

Vegetable glycerin, aloe oil, and a bittering agent were also added. CDC also recommends a small amount of hydrogen peroxide to passivate the container.

Jacob Bisbal, a graduate student in biology, and Alan Martinez, an undergraduate chemistry major, mixed up the first 20-liter batch, for an incredibly thrifty $9 per gallon. They scrounged travel size applicators and spray bottles at area stores, filled, labeled, and distributed them.

“We figured out that it worked pretty well, and we burned through our supplies,” Smith says.

So, Smith turned to Carlos Baca, a senior laboratory services technician in the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry to scale up the enterprise.

“He dispenses from 55-gallon drums of ethanol in the stockroom, so we partnered with them to keep the spigot flowing,” Smith says. “And from there we were able to make five-gallon batches in record time, which can provide sufficient supply to last a department for a couple of weeks.”

As word spread around campus, demand outside the College of Engineering grew, and Smith’s group is actively ramping production to supply hand sanitizer campus-wide.

Smith’s group has also been busy safeguarding the facilities, particularly the research labs.

COVID-19 is spread through airborne aspirated droplets. “If they don’t end up getting inhaled by another human, they will land on something and have a latency of a week or so on most conventional surfaces,” Smith said.

Combating a biosafety level 2 (BSL-2) agent like COVID-19 requires that all porous surfaces such as fabric and bare wood be covered or sealed. All other ‘common’ surfaces, including card readers, doorknobs, computer keyboards/mice, light switches, microscope oculars, etc.—are sanitized at least once a day. Further, access to the labs has been limited to only essential research to maximize social distancing and minimize lab occupancy.

“I am very proud of the researchers at Texas State during this very challenging time. They have continued to focus on carrying out their important research mostly remotely while making sure that students and staff are able to stay safe and healthy. Also, the faculty have continued to submit proposals for funding to support the applied research mission and we have received major awards even during this unprecedented interruption of normal operations. This is very good news because the research mission of the university is not only important for the science but also as a major driver of economic development in the region,” said Dr. Walter E. Horton, associate vice president for Research and Federal Relations.

Smith is quick to say that all the precautions in the world won’t help if someone makes a careless mistake. He says any type of mask is very helpful to protect the user whereas gloves can provide a false sense of security if proper etiquette is not followed.

“If the user has access to that PPE (personal protective equipment) but doesn’t follow strict protocols, like say if someone forgets to wash their hands or reaches up under their mask and scratches their nose, it defeats the purpose. It’s much more about the human behavior than the PPE.”

Smith advises the public to pay attention to CDC guidelines and be aware of how COVID spreads.

“There’s a lot of information flying at everybody,” Smith says. “The CDC guidelines are really important to understand what everyone’s role is to prevent the spread of the virus, how to use a commonsense approach to your personal hygiene and practice hyper awareness of what you’re doing with your hands when you’re in a zone with potential COVID virions. “Just don’t touch your face with your hands until you have washed or sanitized them. That’s the single most important thing you can do.”

Share this article

For more information, contact University Communications:Jayme Blaschke, 512-245-2555 Sandy Pantlik, 512-245-2922 |