Experts warn of summer threat from 'kissing bugs' and Chagas disease

Jayme Blaschke | July 20, 2020

As the summer heats up, experts with the Texas Chagas Taskforce are warning about the threat "kissing bugs" can pose for humans and pets as they spread Chagas disease.

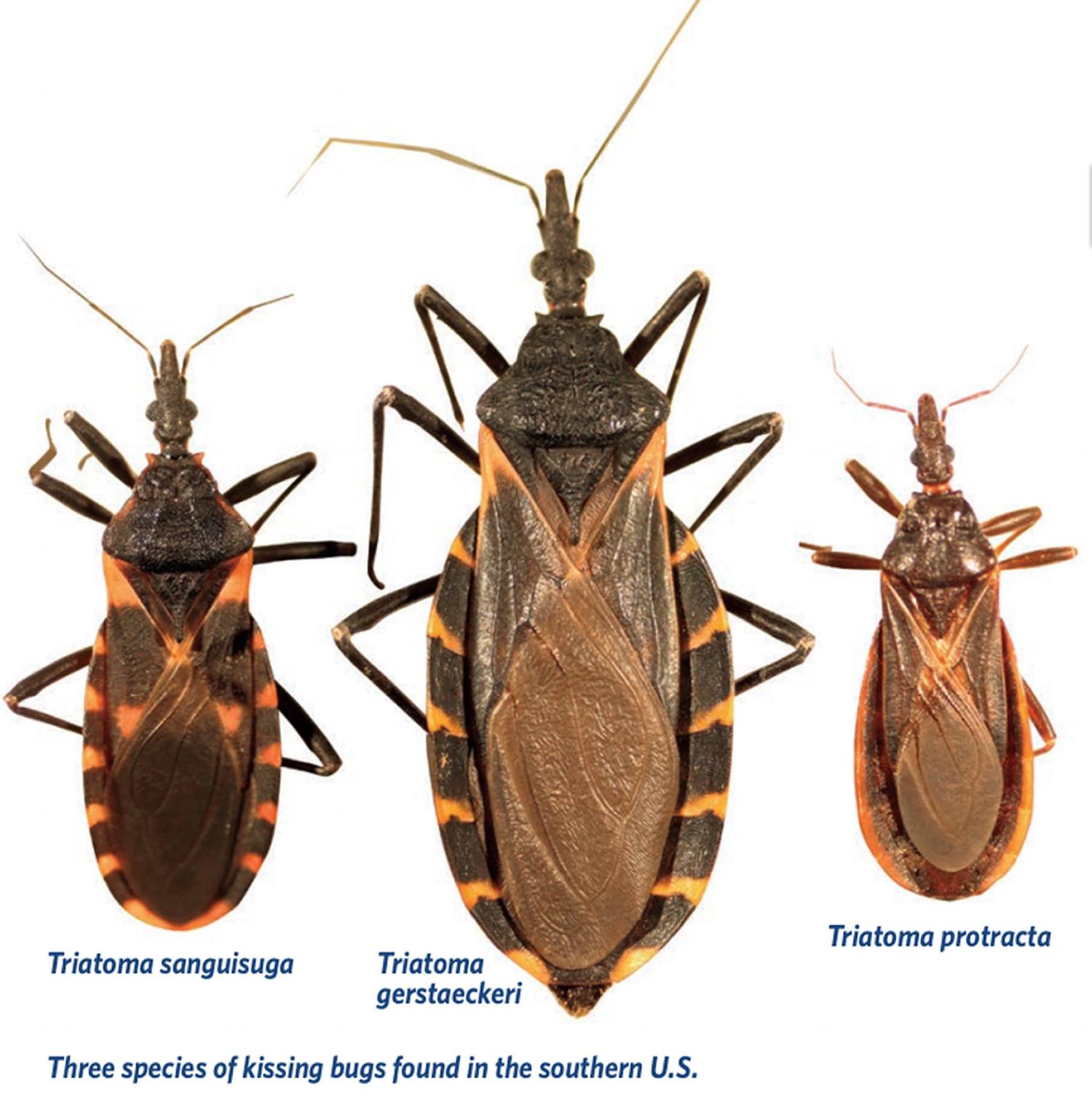

“Kissing bug” is the common name for a group of blood-sucking insects called triatomines. Chagas disease is caused by a parasite, Trypanosoma cruzi, that lives in the intestines and feces of kissing bugs.

"These bugs are found across the Southern United States, Mexico, Central and South America, especially during the hot summer months," said Paula Stigler Granados, assistant professor in the School of Health Administration at Texas State University and lead organizer of the Texas Chagas Taskforce. "This parasite can cause Chagas disease in the people and animals it infects. Although infections from this parasite are not common, approximately 25% of people that are infected develop serious chronic disease, so early diagnosis is important."

The Texas Chagas Taskforce is a group of experts working to raise awareness of this often-neglected disease. As part of that effort, the taskforce is sharing information and resources on Chagas disease and kissing bugs with the public.

Kissing bug boom

There are 11 different kinds of kissing bugs in the U.S., with the majority of reports coming from Arizona, California, New Mexico and Texas. The taskforce is concerned by an unusual growth in the kissing bug population for 2020. The more kissing bugs that are out there, the greater the chance of them coming into contact with humans or pets.

"Our research is suggesting an above-average year for adult kissing bug activity in 2020," said Gabriel Hamer, associate professor in the Department of Entomology at Texas A&M University. "For example, we have collected over 300 adult specimens in a location when last year we had only collected six from that same location. We hope to identify what is causing this increase."

"I have been receiving an unusually large number of photos from people through our Facebook page of kissing bugs people have recently found in and around their homes," Granados said.

Kissing bugs usually feed on blood during the night, when animals or people are asleep or inactive. The bites are often painless and many people do not even realize they have been bitten. Kissing bugs can live indoors, in cracks and holes of housing, or in a variety of outdoor settings including:

- Beneath porches

- Between rocky structures

- Under cement

- In rock, wood, brush piles or beneath bark

- In rodent nests or animal burrows

- In outdoor dog houses or kennels

- In chicken coops or houses

What is Chagas disease?

Chagas disease can be difficult to identify. Many of the people who have the disease do not have symptoms until years or even decades after being infected. Chagas disease has two important phases:

- Acute Chagas disease happens immediately after infections and can last about 8-10 weeks. During this phase, parasites may be found in the circulating blood. This phase of infection is usually mild or with no symptoms at all. Some may experience a fever or swelling around the bite site. It is rare to diagnose Chagas disease during this phase.

- Chronic Chagas disease follows the acute phase. During this phase, parasites are not found in the blood and there are no symptoms. Most people are unaware of their infection and may remain without symptoms for life. However, an estimated 20–30% of infected people will develop severe and sometimes life-threatening medical problems that include heart rhythm abnormalities that can cause sudden death and a dilated heart that doesn’t pump blood well.

Chagas disease can reactivate with parasites found in the circulating blood in people who have suppressed immune systems (for example, due to HIV infection or chemotherapy). Reactivation can potentially cause severe disease. Chagas disease often is a life-long diagnosis; however, there are treatment options available and requires regular follow-ups with your doctor.

Testing bugs

Anyone capturing a kissing bug that is known or suspected of having bitten a person or pet should submit the insect for testing. Many state health departments accept kissing bugs for testing for the parasite that causes Chagas disease, however, the insect must either have been found inside the home or be suspected of having bitten someone.

In Texas, kissing bugs should be sent to Texas Department of State Health Services (TDSHS). Information about how to submit can be found at www.dshs.texas.gov/IDCU/health/zoonosis/Triatomine-Testing.aspx.

If the kissing bug tests positive, it is recommended that anyone potentially exposed to the insect consult a physician about getting tested. A positive diagnosis must be confirmed before any treatment options are provided.

"In addition to infecting people, the parasite can infect a wide range of domestic and wild mammals," said Sarah Hamer, associate professor of epidemiology in the College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences at Texas A&M. "There is increasing recognition for canine Chagas disease especially in Texas, where increasing numbers of household pets, working dogs, and hunting dogs are being diagnosed with Chagas disease."

Animal owners should consult a veterinarian if they suspect a pet may have come into contact with kissing bugs or has Chagas disease.

Any kissing bugs found outside the home and not suspected of biting a human may be sent to Texas A&M University Kissing Bug Citizen Science Program. Submission information may be found at http://kissingbug.tamu.edu.

More work to be done

Stigler Granados has been leading efforts to raise awareness on Chagas disease in Texas for the last several years. Her work with the taskforce has received national recognition and led to several related projects. She is currently wrapping up a 5-year Centers for Disease Control grant focused on raising awareness for Chagas’ disease amongst healthcare providers in Texas. She is starting a pilot project to screen newborns for Chagas’ disease with funding from the international non-profit Mundo Sano (www.mundosano.org/en/).

She is leading online tele-mentoring efforts through an ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes) model to provide education to providers and community health workers on Chagas disease (https://wp.uthscsa.edu/echo/echo-programs/chagas-disease/).

Stigler Granados has recently received a Department of Defense grant to survey the prevalence of Chagas disease-infected kissing bugs near U.S. military bases situated along the border with Mexico (https://news.txstate.edu/featured-faculty/2020/department-of-defense-taps-texas-state-to-study-chagas-disease-threat-to-military-bases.html).

Additional Resources

Anyone seeking to contact the Texas Chagas Taskforce may do so via social media at www.facebook.com/TexasChagasTaskforce on Facebook and @ChagasTexas on Twitter.

Resources for Medical Providers:

- www.dshs.state.tx.us/IDCU/disease/chagas/Chagas-Disease-Information-for-Medical-Providers.aspx

- www.cdc.gov/parasites/chagas/health_professionals/index.html

For more information on Kissing bugs, visit:

- www.cdc.gov/parasites/chagas/gen_info/vectors/index.html

- www.dshs.texas.gov/IDCU/disease/Chagas-Disease.aspx

Resources for pet owners and Veterinarians:

Interview inquiries may be directed to:

- Dr. Paula Stigler Granados psgranados@txstate.edu

- Dr. Gabriel Hamer ghamer@tamu.edu

- Dr. Sarah Hamer shamer@cvm.tamu.edu

Share this article

For more information, contact University Communications:Jayme Blaschke, 512-245-2555 Sandy Pantlik, 512-245-2922 |